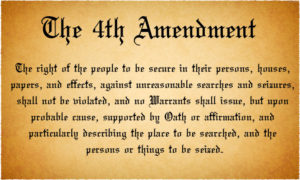

We will start with the Fourth Amendment – search and seizure law. Part 1.1 discusses what the Fourth Amendment says, what it protects and when it applies.

The Fourth Amendment – What it Says and What it Protects

The Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution protects us from unreasonable governmental intrusions into our private domain. In this context, the “domain” includes private spaces and private objects. This is the actual text:

“The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.” U.S. Const. Amend. IV.

What does this mean? It means that: (1) the police must justify any search (or seizure) that was done without a warrant; and/or (2) the police may seek judicial authorization (a warrant) to search (or seize). If the police decide to get court permission (a warrant), then they must show the court that they have probable cause – enough evidence that would lead a reasonable person to believe that the things desired to be searched (or seized) are connected to criminal activity. And, again, if the police search or seize absent a warrant, then they must justify that warrantless intrusion. We will discuss what justifies warrantless intrusions later in this Part.

When Does the Fourth Amendment Apply?

The Fourth Amendment’s protections are not triggered unless and until we have some government actor that initiates a “search” or a “seizure.” The legal terms “search” and “seizure” have precise Fourth Amendment definitions. Thus, police behavior that many believe constitutes a search or a seizure will not activate our Fourth Amendment privacy protections if that conduct falls outside of these precise legal definitions. What constitutes a “search” and what constitutes a “seizure?”

SEARCH

The United States Supreme Court articulated the Fourth Amendment definition of a “search” in Katz v. United States, 389 U.S. 347 (1967). In Katz, federal agents placed a listening device against the wall of a public phone booth that Katz was using and listened in on Katz’s private phone conversation. Katz was discussing an illegal wagering operation and sought to exclude evidence of his phone booth conversation as a violation of his Fourth Amendment rights. The Supreme Court found a “search” within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment even though the listening device was placed on the phone booth exterior. The Court stressed that the focus is not whether the government physically trespassed, but whether the person has a “reasonable expectation of privacy” in the sphere that the police sought to invade. Here, Katz did what he could to make the conversation private – he used an enclosed phone booth. Thus, any attempt to invade that sphere amounted to a “search” within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment. Because the Fourth Amendment was activated, the federal agents in Katz would have had to get a warrant to listen in or justify that it was a reasonable warrantless wiretap.

But, a person with misplaced confidence in a government actor does not have a reasonable expectation of privacy in what would otherwise be a private sphere. What does that mean?

It means that the suspect cannot claim a “search” if he voluntarily offered up information to an undercover government informant or agent. Lewis v. United States, 385 U.S. 206 (1966). In Lewis, an undercover federal narcotics agent misrepresented his identity to Lewis on the telephone, which tricked Lewis into inviting the agent inside his home for the purpose of executing unlawful narcotics transactions. Here, Lewis voluntarily let the agent in his home even though he did so with misplaced confidence. The home would have otherwise been a private sphere, but because Lewis allowed the agent inside, he no longer had a “reasonable” expectation of privacy. This was not a “search” and thus the government did not need to justify it or get judicial approval. As we make our way through this Series, you will notice that, generally speaking, the law allows police officers to lie and deceive during the course and scope of their investigations. Our civil liberties are thus generally insensitive to a suspect’s intellectual capacity.

Also, we generally do not have privacy rights in third party institutional records. What does that mean?

It means that our bank records or telephone records are generally not subject to Fourth Amendment protections. Thus, the government’s attempt to secure our bank records does not constitute a “search.” See e.g., United States v. Miller, 425 U.S. 435 (1976). The bank’s records are the bank’s records – they are not the customer’s private papers. Because the bank owns the records, we have no “reasonable” expectation of privacy in them despite the fact that they are connected to our name.

What about police surveillance on the real property that we own? What constitutes a “search” in this context?

The analysis depends upon where the surveillance happens and how it happens. Generally, the analysis deals with the space in the home, the space immediately surrounding the home (curtilage), and the private property space outside of the curtilage. Thus, I’ll break it down into these three areas.

(1) THE HOME: An individual enjoys the highest expectation of privacy within the home. Any entry into the home is a “search.” To enter the home, the police must have a warrantless justification or judicial approval. I’ll discuss warrantless justifications and warrants themselves later on in the Series.

(2) THE CURTILAGE: An individual enjoys a little less legal privacy within the “curtilage” (the enclosed area immediately surrounding and in close proximity to the dwelling house). Thus, the government’s surveillance of the curtilage from a public vantage point and with the unaided eye is not a “search.” For example, no “search” when the police flew over the suspect’s property and saw a marijuana plot inside the curtilage with the unaided eye. See California v. Ciraolo, 476 U.S. 207 (1986); Florida v. Riley, 488 U.S. 445 (1989). In both cases, the police were not able to see what was inside the curtilage from the ground, but a an easy fly over in public airspace revealed everything with the unaided eye. If the police had trespassed the curtilage on the ground to see what was inside, then we would’ve had “search.” In short, we do not have a “reasonable expectation of privacy” into spaces that can be seen by any member of the public from a public vantage point. We must enclose and protect all four sides of the space to create expectations of privacy.

(3) THE “OPEN FIELD”: An individual can expect the least amount of legal privacy in the “open field” (areas of the private property that are dissociated with the intimacies of the home – e.g. the tool shed). Thus, police officers that trespass the “open field” and discover illegal stuff with the unaided eye is not a “search.” Oliver v. United States, 466 U.S. 170 (1984). In Oliver, the police entered the suspect’s private farm without consent despite the fact that a “no trespassing sign” was posted. Officers sought to investigate whether Oliver was growing marijuana. Officers observed a field of pot with the unaided eye on the farm, but the pot field was more than a mile away from Oliver’s actual dwelling. The pot field was thus beyond the curtilage, in an “open field”, but still on private real property. The Supreme Court held that the police surveillance here was not a “search.” A government trespass on “open field” private property is therefore not a “search.” As such, anything the police can plainly see on this “open field” is fair game without a justification or judicial approval. In order for there to have been a “search” in Oliver, the pot field would have to be enclosed in an opaque way such that the officers would not be able to see inside without certain technology. We have a “reasonable expectation of privacy” in enclosed opaque effects.

What constitutes a “search” with respect to our things, containers or effects?

Generally, if a police officer opens a purse, a bag or a wallet and looks inside, we have a “search.” And, digital manipulation also rises to the level of a Fourth Amendment “search.” Bond v. United States, 529 U.S. 334 (2000). In Bond, border patrol agents squeezed Steven Bond’s soft luggage and manipulated its contents – that was a “search.” If the police want to grab our stuff and squeeze it they need a warrant or some warrantless justification to do so. But, note that if we abandon our stuff in the trash, we lose our expectation of privacy in it – any rummaging within does not equal a “search.” California v. Greenwood, 486 U.S. 35 (1988).

What constitutes a “search” when the police use enhancement devices?

Generally, I’ve noticed the following theme in these cases: If what is observed cannot be seen with the naked eye alone, and can only be discovered with some enhancement device (e.g. binoculars) then it is more possible that we have “search.” This is a general rule however – the setting, manner of observance, and vantage point all play a role in the level of intrusiveness. On the other hand, if the device merely enhances sensory perception and facilitates surveillance that would otherwise be possible without the enhancement, then we usually do not have a “search.”

Let’s take a look at some case examples. A monitoring device surrepticiously inserted into the home for the purpose of tracking movement inside is a Fourth Amendment “search.” United States v. Karo, 468 U.S. 705 (1984). The key here is two fold: (1) the police could not have tracked movement inside the home without the device; and (2) we have a strong American policy to protect the space inside the home. By contrast, a beeper device placed on a car to track the car’s whereabouts is not a “search.” United States v. Knotts, 460 U.S. 276 (1983). In Knotts, the police could have tracked the car’s movement without the beeper – a person traveling in public has no expectation of privacy in his or her movements.

Let me reiterate the general theme with enhancement technology: If the device reveals information within the private sphere that the police could not have surmised without it (i.e. naked eye only), then we usually have a “search.” But, the dog sniff is an isolated exception to this general enhancement device theme. A dog trained to sniff our closed, opaque containers (e.g., luggage at the airport) for contraband within is known as a “surgical strike.” The dog sniff “surgical strike” reveals information about what may be inside the container – information that may be undetectable with the naked eye or nose. Notwithstanding this, the dog sniff is not a “search.” United States v. Place, 462 U.S. 696 (1983). Federal agents used a drug dog to sniff Place’s luggage at the airport for narcotics – the dog alerted agents that drugs were inside Place’s bags. This was not a “search” because the dog (or enhancement mechanism) only reveals the possibility of contraband inside; the dog sniff does not disclose to the police what else may be inside the bag and is thus far less intrusive than, for example, the home tracking device in Karo. The tracking device in Karo was both on the home and broad enough to reveal private facts inside the home that have nothing to do with criminal activity.

SEIZURE

A government “seizure” also triggers the Fourth Amendment. The police can seize people or tangible things. When the police seize us (e.g. detention or arrest) or our things, they must have a warrant or some warrantless justification.

When do we have a “seizure” of the person?

A “seizure” of the person can be brief or long. If the seizure is brief, we have a detention. If the seizure is longer, we have an arrest. Both a detention and an arrest therefore trigger the Fourth Amendment. A police officer must justify a warrantless detention (e.g. pedestrian stop) or a warrantees arrest (taken to the station house for booking). We will discuss what justifies warrantless seizures later in this Series.

A “seizure” of the person occurs when we have the following facts: (1) the government acts intentionally; (2) the suspect actually submits to some showing of government authority; and (3) a reasonable person would feel that he or she could not leave and/or otherwise terminate the encounter.

(1) The Government Acts Intentionally: The seminal decision is Brower v. County of Inyo 489 U.S. 593 (1989). In Brower, officers were engaged in a high speed chase and intentionally placed roadblocks ahead to arrest the suspect’s movement. The roadblock was set up around a blind turn. Brower did not see the roadblock, lost control, crashed and died. Here, the police did not intend to cause the ultimate seizure if you will – death. Instead, officers intended to stop Brower’s movement. This amounted to a “seizure” because the government intentionally applied means to interfere with a person’s movement. It is irrelevant that officers did not intend to cause Brower to crash. Thus for example, if an officer inadvertently tripped someone, we would not have a “seizure.” The government must intend to seize for us to have a “seizure” within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment.

(2) The Suspect Actually Submits to Authority: The famous case on this element is California v. Hodari D., 499 U.S. 621 (1991). Hodari saw some police officers pull up so he tossed his stash and ran. Officers picked up the stash and ultimately caught Hodari. Hodari tried to claim that at the point he threw his stash and ran, he was “seized.” The Supreme Court disagreed and ruled that we must actually submit to authority in order to have a “seizure.” This means that when physical pressure is applied and/or the suspect surrenders, we have a “seizure.” Therefore, a “seizure” occurred in Hodari when the police actually tackled and arrested him (i.e. physical pressure). ***You may be wondering why the timing of when a “seizure” takes place matters. The timing of when a “seizure” happens is important because the Fourth Amendment applies at that point. And, when the Fourth Amendment applies, we must have a warrant or some warrantless justification for the government’s behavior to ensure the evidence secured by way of that “search” or “seizure” is admissible. If the Fourth Amendment is not in play, then officers do not need judicial approval or some legal justification for their behavior. Remember the exclusionary rule I explained in the Introduction: evidence discovered by way of an illegal “search” or “seizure” is not admissible in court.

(3) A Reasonable Person Would Feel That He or She Could Not Leave and/or Otherwise Terminate the Encounter: Some important decisions, among others, on this subject are Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1 (1968), Florida v. Royer, 460 U.S. 491 (1983), Florida v. Bostick, 501 U.S. 429 (1991), United States v. Mendenhall, 446 U.S. 544 (1980), United States v. Drayton, 536 U.S. 194 (2002), Kaupp v. Texas, 538 U.S. 626 (2003). There is no bright line rule as to when a reasonable person would feel as if he or she could not leave and/or otherwise terminate the encounter. But, to help guide you in your quest to know your rights, I would note the following theme: If the police leave you no choice and/or interfere with your movement in some way, then we likely have “seizure.” If you have a choice and/or the police do not intentionally restrict your movement, then we likely do not have a “seizure.” The latter scenario is usually referred to as “consensual encounter” in the criminal courts. A “consensual encounter” therefore does not trigger the Fourth Amendment. The police are allowed to talk to us and ask us questions without a warrant or some legal justification. But, when the police tell us to sit on the curb while they check our identification, we likely have a “seizure” thus requiring a warrant or some warrantless justification. And, when the police put us in cuffs and take us to the station, we definitely have a “seizure.” An arrest is always a “seizure.” A detention is always a “seizure.” I will discuss the legal differences between an arrest and a detention later in this Series.

When do we have a “seizure” of things or chattels?

What is a chattel? A chattel is a personal possession. A “seizure”of a chattel occurs when we have a substantial and/or meaningful governmental interference with someone’s possessory interest. United States v. Jacobsen, 466 U.S. 109 (1984). In Jacobsen, a DEA agent removed a tube containing bags of cocaine from a larger cardboard box. That DEA behavior was a substantial interference with the cardboard box (chattel), and thus a “seizure” necessitating judicial approval or some warrantless exception to justify the cocaine coming into evidence. In the Karo case discussed above, the tracking device was not a “seizure” because its placement constituted a technical trespass as opposed to a meaningful interference in an ownership interest. Similarly, it is not a “seizure” for officers to pick up a stereo for a brief second to obtain the serial numbers on the bottom. Arizona v. Hicks, 480 U.S. 321 (1987). In sum, we do not have black or white rules for when a “search” or a “seizure” occurs. Every analysis in criminal procedure is case by case. We must look at what the courts have said in the past and analogize or distinguish those matters to the case at hand. Cases in the past are referred to as “precedent.” Case precedent is law. And the notion of studying past cases to decide future cases is referred to as “stare decisis.” That of course is Latin. We have lots of Latin in our American judicial system.

STANDING

Even if the police conduct a “search,” a defendant may not have the legal right to challenge it in court. Only those who are actual victims of a “search” can move to suppress evidence. This means that the area in which the evidence is seized must be an invasion of the defendant’s privacy. In other words, if we do not have a personal connection (i.e. some “reasonable expectation of privacy”) to the place searched, then we cannot complain about the evidence seized there, even if it was discovered illegally. This rule is known as “standing.” In court, we say the client has “standing” to challenge the “search,” because the evidence was found in a place where the client had an expectation of privacy. The standing principle derives from Rakas v. Illinois, 439 U.S. 128 (1978). In Rakas, a passenger in another person’s car was challenging the admissibility of a rifle found under the passenger seat as well as box shells in the glove box. Rakas did not have standing to challenge the search because he did not own the car nor did he own the evidence found. But, having a possessory interest in the evidence found does not, by itself, create an expectation of privacy in the area in which the evidence was seized. Rawlings v. Kentucky, 448 U.S. 98 (1980). In Rawlings, the defendant challenged drugs found in his friend’s purse. Rawlings certainly owned the drugs, but he had no other connection to the purse, and thus he did not have standing to challenge anything found inside of it. Rawlings had only known the purse owner for a few days at the time he hid his drugs in her purse; he had never sought nor received access to the purse before; and he had no right to exclude others from access to the purse. But, once we start dealing with places where people stay, then the standing argument becomes stronger. For example, an overnight social guest in another person’s home has access to challenge evidence found inside. Minnesota v. Olson, 495 U.S. 91 (1990). But, a mere business guest in one’s home does not grant that business guest standing to challenge evidence seized inside. Minnesota v. Carter, 525 U.S. 83 (1998).